Cucumber, Chai, and JSDOM

Table of Contents

What Is This About?

The Earlier Problem

In my code from my spiral post I used document.getElementById as a check to make sure that I was passing in a valid div ID to p5.js and I decided to add some testing to make sure my validator was working as I expected. The problem was that when you run tests in node.js the document object doesn't exist. One way to get around this might be to use Selenium or some other browser-tester but that seemed like overkill.

My first idea was that I would just mock the document object using sinon since this is a fairly easy thing to do in python (maybe not mocking document, specifically, since that is a javascript thing, but mocking objects in a module is fairly easy) but I simply couldn't find anything that seemed to indicate that this was possible, only posts saying that sinon doesn't work that way.

So then I stumbled upon jsdom, which appeared to be what I wanted to mock the document. The problem was that it's more of a browser simulator not a means to replace objects so I still had to figure out a way to replace the document that my class was expecting with the jsdom document. In the other post where I first used jsdom I followed the pattern shown in this github repository where you stick the jsdom document into the global variable which makes it appear to be a global variable just like it is when you run the code in a browser.

global.document = dom.window.document;

Where dom is an instance of jsdom setup with some HTML to use for the testing. Amazingly this did seem to work…

The Newer Problem

Then I got to this post where I wanted to document getting jsdom to work and, even though I was using a simpler version of the previous post, I found that the tests were failing mysteriously (pretty much everything with javascript is mysterious to me). With a lot of troubleshooting, I managed to find out that instead of using the dom I was creating here it was still using the same one from the other testing. Except sometimes it was using the dom I defined here and these tests passed but then the other tests failed. I guess global means global in the truer sense, not just for the scope of a single set of tests, and there's some kind of race going on between the different pieces of code that are trying to set and use this global document. Oy.

So, then I went looking at the jsdom documentation (which is pretty much just a readme and all the "issues" people have posted), but there was one page on their wiki titled Don't Stuff jsdom Globals Onto the Node Global, which, I guess, means that I shouldn't have done what I did and all those Stack Overflow answers say to do. The page scolding all us silly people for using global did have a few examples of how they thought you should do it instead, so then I tried their solution of adding the javascript for my class to the jsdom object instead of using it in the cucumber.js test code. That way my class would have access to the document in their global space.

Easy-peasy. Well… this produced more mysterious failures except now it was in a different place. After running their examples in the Node REPL unsuccessfully I found this "issue" where it's explained that they don't support the <script type="module"> parameter (so you can't use ES6 imports like I do). Okay, so then I dumped the class definition to a string and added it directly, but no matter what I couldn't get jsdom to interpret any class I put in, although functions did work, so I came to the conclusion that they don't support javascript classes either.

I couldn't find anything specific about not supporting classes, but trying to search using terms like class and document brings up so much irrelevant stuff that it's maddening to even look for anything so there might have been some skimming fatigue that blinded me to any documents about it, if they existed.

But then, while fiddling with the Node REPL I found that defining the document before instantiating my class made it work, so I thought, okay, why am I trying so hard to do all this patching when I can just create the document object in my tests and then create the object under test? Well, the answer to that is - "because it doesn't work". For some reason the document object existed before and after creating my test object but it was always undefined within the class method I was testing. Mysterious.

In the end I ended up doing an ugly workaround which didn't really even require using jsdom, although I guess using it at least validates that I'm using the right method name… Anyway, here it is.

The Feature File

This is a Cucumber.js test so I'll create a simple feature file for a class that retrieves a document element and test the case where the ID is correct and the one where it is incorrect.

Feature: An Element Getter

Scenario: A Valid ID

Given an ElementGetter with the correct ID

When the element is retrieved

Then it is the expected element.

Scenario: The wrong ID.

Given an ElementGetter with the wrong ID

When the element is retrieved using the wrong ID

Then it throws an error.

The Software Under Test

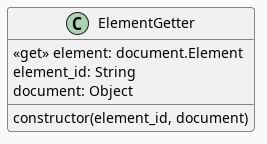

Now the implementation. This is kind of a useless class, but this was supposed to be about how to get jsdom working so I can test code expecting a document.

The Class Declaration

This is the class I'm going to test.

class ElementGetter {

#element;

constructor(element_id, document) {

this.element_id = element_id;

this.document = document;

};

The constructor shows the main change I made to get it working - instead of using a global document I added it as an argument. I went through all that rigamarole trying to avoid this since it seemed like I was changing code just to test it, but now that I think about it, it's what I'd've done in python anyway, since I kind of don't like these "magic" objects that show up without being created or imported like they do in javascript.

The Get Element Method

I made a getter for the retrieved element. It probably would have been easier in this case if I didn't store it, since I could test both when the ID is correct and when it isn't with the same object, just by changing the this.element_id value, but it's a pattern I often use and it gave me the chance to test out javascript's Private Class Fields syntax. To be quite honest, I think using the pound sign (#) is kind of ugly - I prefer the underscore, and Pygments draws red boxes around the #- but at least I know about it.

The main value in using a getter here is that it can check that the element exists, since an invalid ID passed to getElementById will just return a null object rather thhan throw in error.

get element() {

if (!this.#element) {

this.#element = this.document.getElementById(this.element_id);

if (!this.#element) {

throw Error(`Unable to pull the element with ID '${this.element_id}'`);

};

};

return this.#element;

};

The Step File

And now the test code.

Setting Up

Import the Test Libraries

import { expect } from "chai";

import { Given, When, Then } from "@cucumber/cucumber";

import { JSDOM } from "jsdom";

These are the libraries that I installed to support testing. Using jsdom instead of creating a mock was convenient, but I might have to watch what the overhead is if I make a lot of tests that use it.

Import the Software Under Test

Now I'll import the ElementGetter class that I defined above. It occurs to me that for a case like this where I don't actually use the code for anything other than testing I could have put it next to the tests, but I guess this is a better dress rehearsal for really using code in a post.

Note the extra step up the path (../) because this time I followed the cucumber example and put the steps in a folder named steps instead of in a file named steps.js, which might make it easier to organize in the future if I have more to test, but makes relative paths that much more painful.

import { ElementGetter } from "../../../../files/posts/cucumber-chai-and-jsdom/puller.js";

Setup JSDOM

Here's where I create the jsdom object with a div that the ElementGetter can get. I'm passing in the whole HTML string but in the documentation they sometimes just pass in the body.

const EXPECTED_ID = "expected-div";

const document = (new JSDOM(`<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<div id='${EXPECTED_ID}'></div>

</body></html>`)).window.document;

The Tests

The Right ID

This is the first scenario where I expect the ElementGetter to successfully find the element. There's not a lot to test here, other than it doesn't crash.

Given("an ElementGetter with the correct ID", function() {

this.puller = new ElementGetter(EXPECTED_ID, document);

});

When("the element is retrieved", function() {

this.actual_element = this.puller.element;

});

Then("it is the expected element.", function() {

expect(this.actual_element.id).to.equal(EXPECTED_ID);

});

The Wrong ID

This is the more interesting case where we give the ElementGetter an ID that doesn't match any element in the page.

Given("an ElementGetter with the wrong ID", function() {

this.puller = new ElementGetter(EXPECTED_ID + "abc", document);

});

Since I made a getter to retrieve the element, you can't pass it directly to chai to test - trying to pass this.puller.element to chai will trigger the error before chai gets it - so instead I'm using something I learned working with pytest. I'm creating a function that will retrieve the element and then passing the function to chai to test that it raises an error.

When("the element is retrieved using the wrong ID", function() {

this.bad_call = function(){

this.puller.element

}

});

Then("it throws an error.", function() {

expect(this.bad_call).to.throw(Error);

});

What Have We Learned?

I suppose the biggest lesson is that I shouldn't have tried so hard to fake the document object as a magic global object the way it normally is used and instead just gone for an explicit argument that gets passed to the class (or function) that needs it (which sort of follows the Dependency Injection Pattern). I also learned that jsdom is interesting but behind the ECMA standard, as were some of the other libraries I ran into in trying to solve different parts of this problem, so I have to either decide to not use ECMA 6 or not rely so much on these other libraries that don't use the current standards.