Compare and Learn

i#t+BEGIN_COMMENT .. title: Compare and Learn .. slug: compare-and-learn .. date: 2018-10-26 10:54:02 UTC-07:00 .. tags: grokking,gradient descent .. category: Grokking .. link: .. description: Introduction to Gradient Descent. .. type: text #+END_COMMENT

Table of Contents

Imports

From PyPi

from graphviz import Digraph

import matplotlib.pyplot as pyplot

import numpy

import pandas

import seaborn

Setup the plotting

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format='retina'

seaborn.set(style="whitegrid")

FIGURE_SIZE = (14, 12)

What is this about?

The three main steps in training a model are:

- Predict

- Compare

- Learn

Forward Propagation was about the Predict step - we fed some inputs to a network and it output its predictions. Now we're going to look an steps 2 and 3 - Compare and Learn, the steps where we figure out how to improve the weights in our network.

What's the next step after Predict?

As noted above, step 2 is Compare meaning compare our predictions with what we know to be the real answers (so this is supervised learning) and see how well (or bad) we did.

Okay, but then what?

After Compare we move on to the Learn step where we adjust the weights based on the errors we found in Compare. In this case we'll use Gradient Descent to find new weights for the network.

So, how do we find the error again?

There are many different ways to measure error, each with different positive and negative attributes, but in this case we're going to use Mean Squared Error. Here's an example with one measurement.

weight = 0.5

input_value = 0.5

expected = 0.8

actual = weight * input_value

# you implicitly divide by 1 to get the mean of the square

actual_error = (expected - actual)**2

expected_error = 0.3

assert abs(expected_error - actual_error) < 0.01

print("Error: {:.2f}".format(actual_error))

Error: 0.30

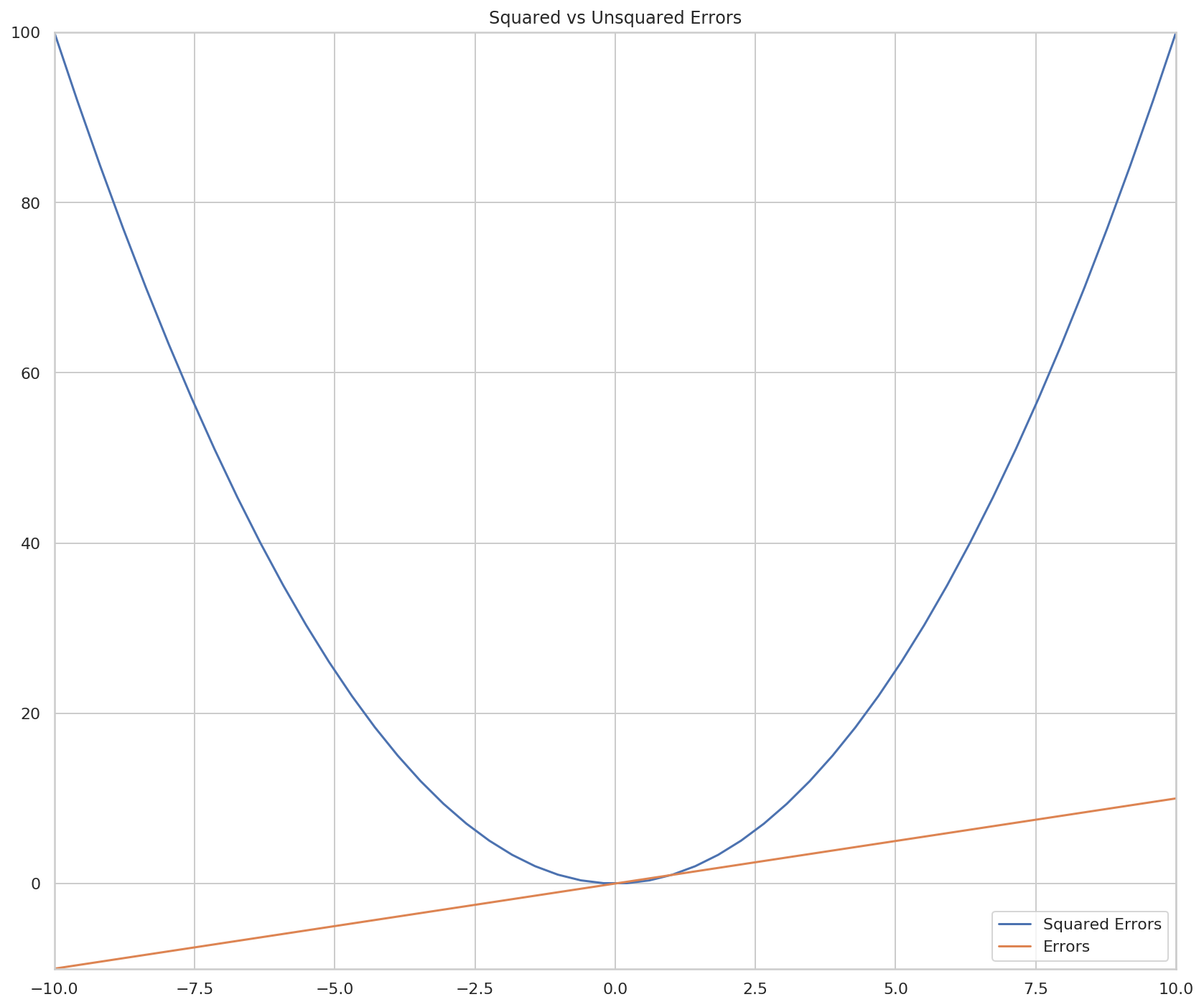

Two things to note about the consequences of squaring the error - one is that it's always positive which is useful because you might have both positive and negative errors which would tend to cancel each other out when you take the mean (the actual_error above is a mean with an implied count of 1), even though both positive and negative errors are wrong, the other consequence is that the greater the error, the larger it grows (it follows a parabola instead of a line).

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

errors = numpy.linspace(-10, 10)

outputs = numpy.square(errors)

axe.set_xlim((-10, 10))

axe.set_ylim((-10, 100))

axe.set_title("Squared vs Unsquared Errors")

axe.plot(errors, outputs, label="Squared Errors" )

axe.plot(errors, errors, label="Errors")

legend = axe.legend()

So how do we learn?

One method is Hot-and-Cold Learning. With this method you move your weights a little and pick the one that improves the error-rate. This first example will go back to the one feature network that tries to predict if a team will win using the average number of toes they have.

graph = Digraph(comment="Toes", format="png")

graph.attr(rankdir="LR")

# input layer

graph.node("a", "Toes")

# output layer

graph.node("b", "Win")

# edge

graph.edge("a", "b", label="Weight")

graph.render("graphs/toes_model.dot")

graph

def toes_model(toes: int, weight: float=0.1) -> float:

"""Predicts if the team will win based on the number of toes

Return:

predction: probability of winning

"""

return toes * weight

def print_error(predicted: float, actual: int, label: str="Toes Model",

separator: str="\n") -> float:

"""Prints the (mean) squared error

Args:

predicted: what the model predicted

actual: whether the team won or not

label: something to identify the model

separator: How to separate the output

Returns:

mse: the error

"""

error = (actual - predicted)**2

print(separator.join([label,

"Predicted: {:.2f}".format(predicted),

"Actual: {}".format(actual),

"MSE: {:.4f}".format(error)]))

return error

toes = 8.5

actual = 1

predicted = toes_model(toes)

error_original = print_error(predicted, actual)

Toes Model Predicted: 0.85 Actual: 1 MSE: 0.0225

So our model has a Mean Squared Error of around 0.02, how do we make it better with the Hot and Cold Method? By trying a larger and smaller weight and using the one that makes the error smaller.

weight_change = 0.01

weight = 0.1

knob_turned_up = toes_model(toes, weight + weight_change)

knob_turned_down = toes_model(toes, weight - weight_change)

error_up = print_error(knob_turned_up, actual, "Turned Up")

print()

error_down = print_error(knob_turned_down, actual, "Turned Down")

Turned Up Predicted: 0.94 Actual: 1 MSE: 0.0042 Turned Down Predicted: 0.77 Actual: 1 MSE: 0.0552

Looking at the error, it looks like making the weight higher improved the score, so we should adjust our weight upwards.

if error_original > error_up or error_original > error_down:

change_direction = -1 if error_down < error_original else 1

weight_updated = weight + change_direction * weight_change

prediction = toes_model(toes, weight_updated)

error_update = print_error(prediction, actual, "Updated Model")

assert error_update < error_original

else:

print("Model didn't improve.")

Updated Model Predicted: 0.94 Actual: 1 MSE: 0.0042

So, this is what machine learning is really about, finding the parameters that give the best prediction. This is why it is often called a search problem - each of your parameters can have a variety of weights (infinite, actually) so what you are doing when you train your model is searching the space of weights to find the set that gives the best outcome for your metric. In this case we are looking to minimize our Mean Squared Error.

Training the Model

Rather than than trying to do the checks one at a time, we can run the Hot and Cold Learning in a loop to tune our model.

weight = 0.5

input_value = 0.5

actual = 0.8

weight_change = 0.001

prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight)

print_error(prediction, actual, "Step 1 Weight: {}".format(weight), "\t")

errors = []

weights = []

optimal_step = False

tolerance = 0.1**8

for step in range(1, 2001):

prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight)

error = (print_error(prediction, actual,

"Step {:4} Weight: {:.2f}".format(step, weight), "\t")

if not step % 100 else (prediction - actual)**2)

errors.append(error)

if not optimal_step and error < tolerance:

optimal_step = step - 1

up_prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight + weight_change)

down_prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight - weight_change)

up_error = (up_prediction - actual)**2

down_error = (down_prediction - actual)**2

direction = -1 if down_error < up_error else 1

weight += direction * weight_change

weights.append(weight)

print("Optimum Reached at Step {}".format(optimal_step))

Step 1 Weight: 0.5 Predicted: 0.25 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.3025 Step 100 Weight: 0.60 Predicted: 0.30 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.2505 Step 200 Weight: 0.70 Predicted: 0.35 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.2030 Step 300 Weight: 0.80 Predicted: 0.40 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.1604 Step 400 Weight: 0.90 Predicted: 0.45 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.1229 Step 500 Weight: 1.00 Predicted: 0.50 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0903 Step 600 Weight: 1.10 Predicted: 0.55 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0628 Step 700 Weight: 1.20 Predicted: 0.60 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0402 Step 800 Weight: 1.30 Predicted: 0.65 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0227 Step 900 Weight: 1.40 Predicted: 0.70 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0101 Step 1000 Weight: 1.50 Predicted: 0.75 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0026 Step 1100 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1200 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1300 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1400 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1500 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1600 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1700 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1800 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 1900 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 2000 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Optimum Reached at Step 1100

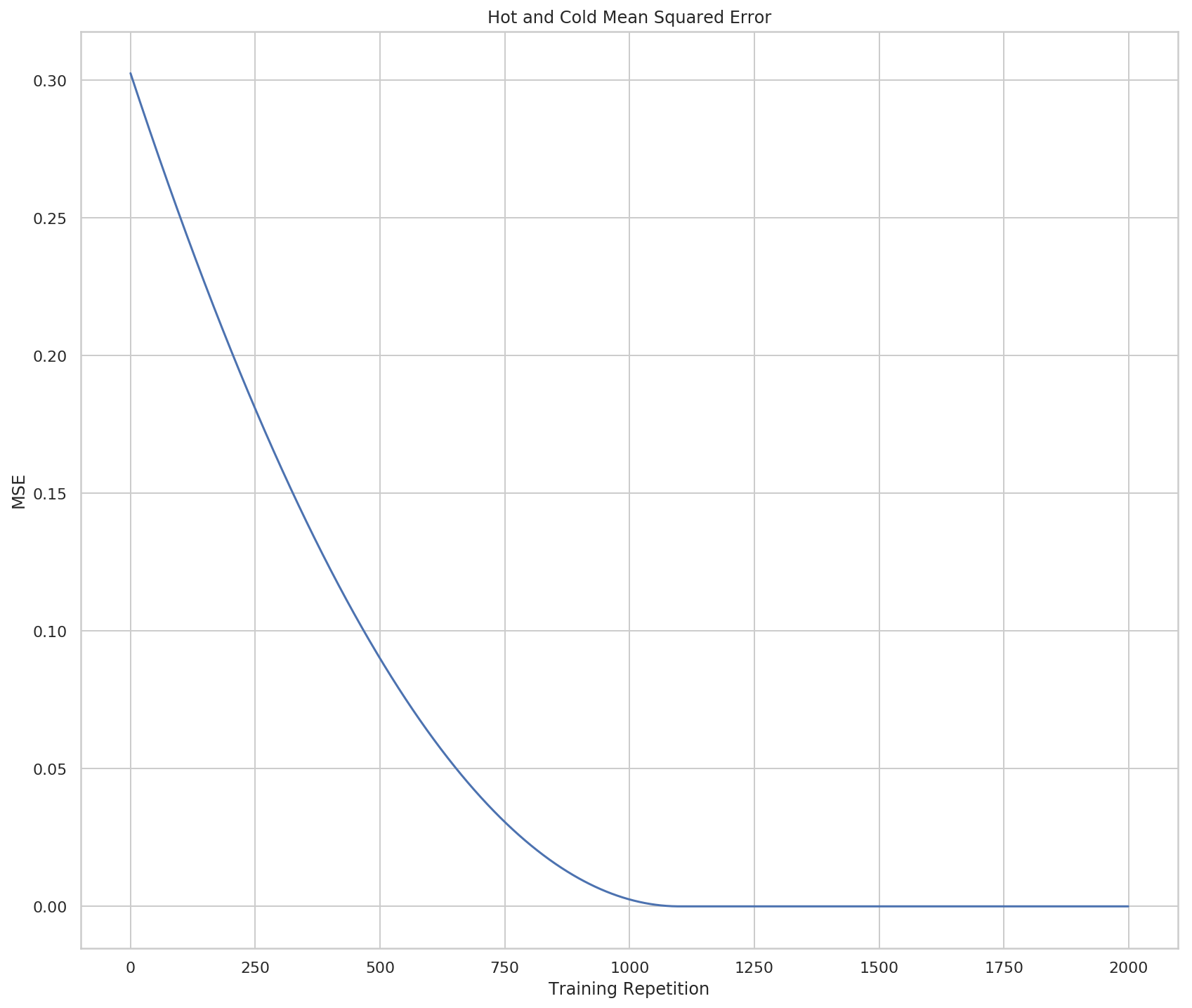

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Hot and Cold Mean Squared Error")

axe.set_xlabel("Training Repetition")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

lines = axe.plot(range(len(errors)), errors)

Looking at the output you can see that it reached an error of (nearly) zero at the 1,100th repetition. Based on the plot it looks like it kind of slowed down at the end, which is odd since we're using addition and subtraction, but I guess as the weight gets bigger the proportion of change you add becomes less.

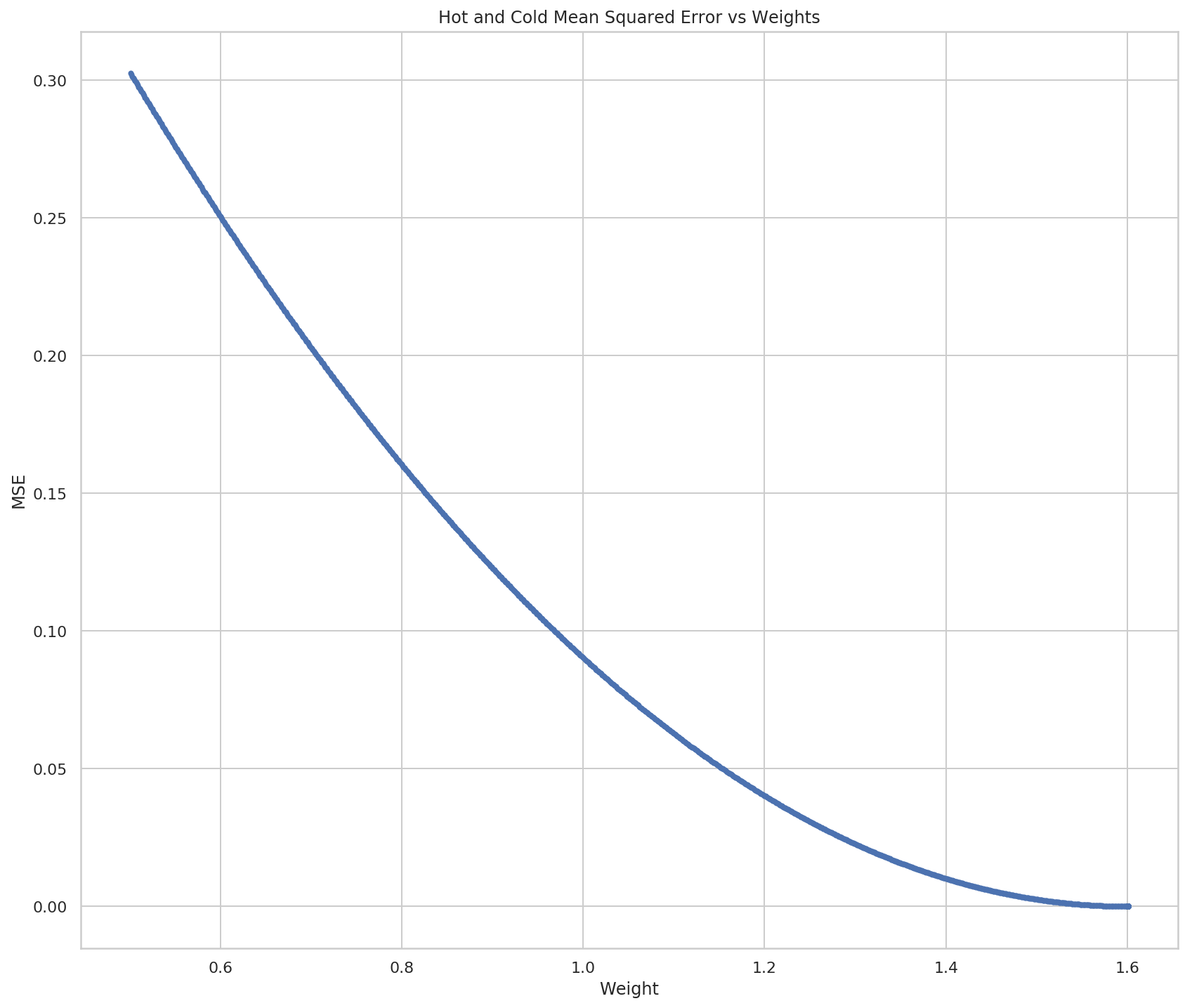

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Hot and Cold Mean Squared Error vs Weights")

axe.set_xlabel("Weight")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

lines = axe.plot(weights, errors, ".")

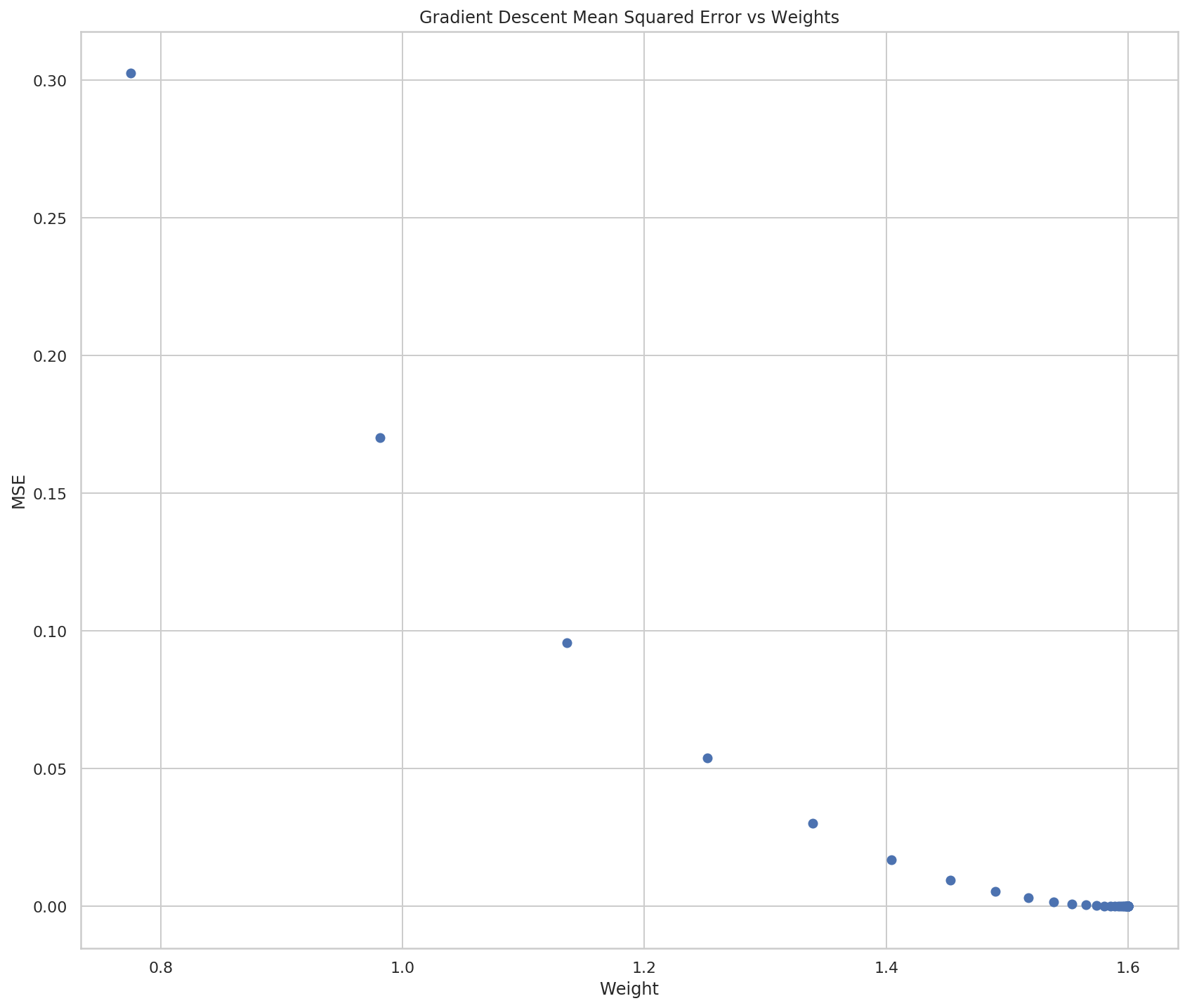

Our optimal weight appears to be 1.6. Given the simplicity of our model we can check by solving the equation.

\[ prediction = weight \times input\\ weight = \frac{prediction}{input} \]

print(prediction/input_value)

1.6009999999999343

So, that looks about right.

Pros and Cons of Hot and Cold Learning

The main thing that Hot and Cold Learning has going for it is that it is simple to understand and implement. There are a couple of problems with it though:

- You have to make multiple predictions per knob to make a decision on the change to make.

- The amount you change the weight at each step can make it impossible to get the right weight, and in most cases you won't have just one input value so it's hard to know what to pick

Is there a better way to update the weights?

With Hot and Cold Learning we make multiple predictions to decide which direction to add a set amount to the weight. But we can instead use the error to change our weight, and in doing so we will change both direction and scale based on the error. In this case error means "pure error", or just the difference between the prediction and the actual value.

\[ error = prediction - actual \]

Since we don't square it the error will be positive if our prediction is too high and negative if it is too low. We don't want to just use the difference, though, because we are adjusting a weight that gets multiplied by the input, so we need to scale the amount of change by the input.

Note that the ordering is now important - you have to subtract the error in the version above and add it if the terms are switched.

\[ adjustment = error * input\\ weights' = weights - adjustment \]

This is the method of Gradient Descent. This is how it looks run on our previous problem.

weight = 0.5

input_value = 0.5

actual = 0.8

prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight)

print_error(prediction, actual, "Step 1 Weight: {}".format(weight), "\t")

errors = []

weights = []

optimal_step = False

tolerance = 0.1**8

optimal_count = 0

print_every = 5

stop_after = 30

for step in range(1, 2001):

prediction = toes_model(input_value, weight)

difference = (prediction - actual) * input_value

weight -= difference

weights.append(weight)

error = (print_error(prediction, actual,

"Step {:4} Weight: {:.2f}".format(step, weight), "\t")

if not step % print_every else (prediction - actual)**2)

errors.append(error)

if not optimal_step and error < tolerance:

optimal_step = step - 1

if error < tolerance:

optimal_count += 1

if optimal_count >= stop_after:

break

print("Optimum Reached at Step {}".format(optimal_step))

Step 1 Weight: 0.5 Predicted: 0.25 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.3025 Step 5 Weight: 1.34 Predicted: 0.63 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0303 Step 10 Weight: 1.54 Predicted: 0.76 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0017 Step 15 Weight: 1.59 Predicted: 0.79 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0001 Step 20 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 25 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 30 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 35 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 40 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 45 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 50 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 55 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Step 60 Weight: 1.60 Predicted: 0.80 Actual: 0.8 MSE: 0.0000 Optimum Reached at Step 30

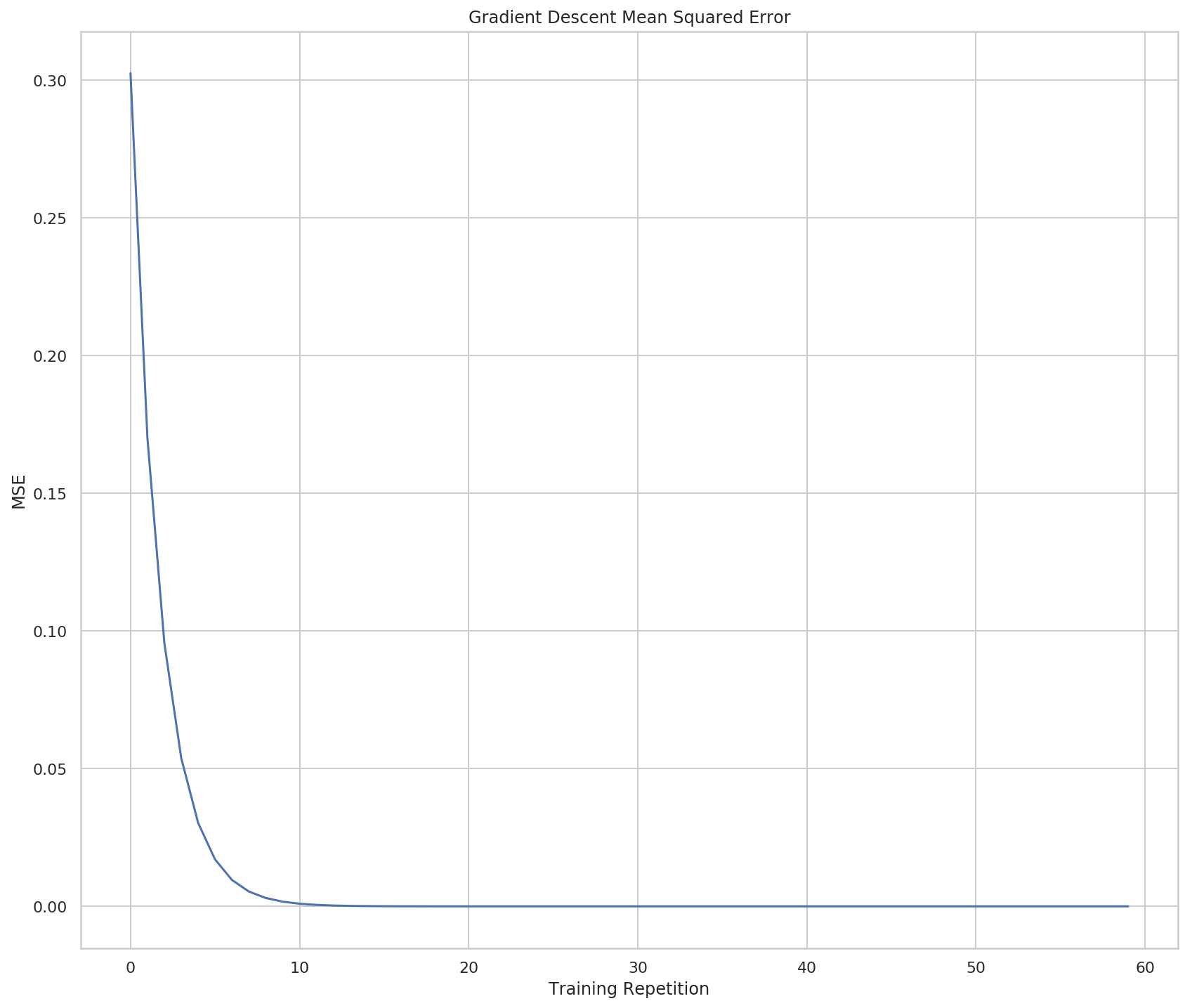

So it now hits the optimal solution at the 30th step instead of the 1,100th step (although it really seems to reach it at step 20, I think the difference is a rounding problem).

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Gradient Descent Mean Squared Error")

axe.set_xlabel("Training Repetition")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

lines = axe.plot(range(len(errors)), errors)

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Gradient Descent Mean Squared Error vs Weights")

axe.set_xlabel("Weight")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

lines = axe.plot(weights, errors, "o")

The plots show what we already saw in the output, that Gradient Descent converges on a solution much faster than Hot and Cold Learning does.

Why multiply the error by the input?

This has three main effects called stopping, negative reversal, and scaling.

What is Stopping?

Stopping refers to the case where the input is 0. If that's the case then we don't want to adjust the weight so multiplying the error by the input nullifies it.

What is Negative Reversal?

The sign of the input changes which direction we want the weight to change, so multiplying it by the input keeps the change moving in the right direction even when the sign of the input changes.

What is Scaling?

The larger the input, the greater the amount of change it will add. This can be a bad thing, since the inputs can now have an outsized (negative) effect.

A Discursion On Derivatives

What we're doing when we train our model to minimize our error. In the Mean Squared Error equation:

\[ MSE = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n ((input \times weight) - actual)^2 \]

The only thing we can change is the weight, the input and actual output is set by the data. So what we're interested in is how the error changes as we change the weight. The relationship between how the output changes in relationship to how the input changes is the derivative. One way to think of the derivative is the slope at a point on a line. If you have a straight line the slope will be the same everywhere on it, but if it is curved then different points will have different slopes.

In our case our input is the weight and the output is the error. If you think about slope as \[\frac{rise}{run}\] you'll notice that the bigger the rise, the bigger the slope (since we're taking it at a point the run is infinitesimal), and it's positive going up and negative going down, so if you think of the plot of the MSE earlier, the further you go away from the center (where the error is zero), the steeper the slope, and moving away from the center is always moving up, so the slope is always positive, and moving toward the center where the error is zero is always moving down, so the slope is negative.

What we want, then, is to move our weights in the opposite direction of the slope. There's more math involved to explain this than I can handle right now, but when we calculate our weight adjustment, we are calculating the derivative, and since we want to move in the opposite direction of the derivative, we negate it. And the further away we are from the true value (where our error is zero), the greater the difference is, as we would expect from the slope of our line.

\[ \Delta = prediction - actual\\ \Delta_{weighted} = \Delta \times input\\ weight' = weight - \Delta_{weighted} \]

When does this work?

Well, it's easier to look at when it doesn't work than when it does.

class OneNode:

"""Implements a single-node network

Args:

weight: the starting weight for the edge from the input to the output

input_value: the input to the node

actual: the actual output we are trying to predict

training_steps: how many times to train the model

tolerance: how close to zero we need our error to be

print_every: how often to print training status

stop_after: how many times to keep going after the optimal was found

"""

def __init__(self, weight: float,

input_value: float,

actual: float,

training_steps: int=200,

tolerance: float=0.1**8,

print_every: int=5, stop_after: int=30) -> None:

self.original_weight = weight

self.weight = weight

self.input_value = input_value

self.actual = actual

self.training_steps = training_steps

self.tolerance = tolerance

self.print_every = print_every

self.stop_after = stop_after

self._errors = None

self._weights = None

self._predictions = None

return

@property

def errors(self) -> list:

"""list of MSE values"""

if self._errors is None:

self._errors = []

return self._errors

@property

def weights(self) -> list:

"""List of weights built during training"""

if self._weights is None:

self._weights = [self.weight]

return self._weights

@property

def predictions(self) -> list:

"""List of predictions made"""

if self._predictions is None:

self._predictions = []

return self._predictions

@property

def prediction(self) -> float:

"""The current model's prediction"""

return self.weight * self.input_value

def mean_squared_error(self) -> float:

"""The mean squared error for the prediction"""

try:

self.predictions.append(self.prediction)

return (self.prediction - self.actual)**2

except OverflowError as error:

print(error)

print("prediction: {}".format(self.prediction))

print("actual: {}".format(self.actual))

return

def print_error(self,

step: int,

separator: str="\t",

force_print: bool=False,

store_error: bool=True) -> float:

"""Prints the (mean) squared error

Args:

step: what step this is

separator: How to separate the output

force_print: ignore the step count and print anyway

store_error: whether to add to the errors

Returns:

mse: the error

"""

error = self.mean_squared_error()

if store_error:

self.errors.append(error)

if force_print or not step % self.print_every:

print("Input: {} Actual Output: {}".format(self.input_value,

self.actual))

print(separator.join(["Step: {}".format(step),

"Weight: {}".format(self.weight),

"Predicted: {:.2f}".format(self.prediction),

"MSE: {:.4f}".format(error)]))

return error

def adjust_weight(self) -> None:

"""Takes the gradient descent step"""

scaled_derivative = (self.prediction - self.actual) * self.input_value

self.weight -= scaled_derivative

self.weights.append(self.weight)

return

def train(self):

"""Trains our model on the values

"""

self.reset()

prediction = self.weight * self.input_value

optimal_step = optimal_count = 0

error = self.print_error(1,

force_print=True,

store_error=False)

for step in range(1, self.training_steps + 1):

error = self.print_error(step)

if error is None:

return

self.adjust_weight()

if not optimal_step and error < self.tolerance:

optimal_step = step - 1

if error < tolerance:

optimal_count += 1

if optimal_count >= self.stop_after:

break

print("Optimum Reached at Step {}".format(optimal_step))

return

def plot_errors_over_time(self, scale="linear") -> None:

"""Plots the error as it is trained

Args:

scale: y-axis scale

"""

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Gradient Descent Mean Squared Error")

axe.set_xlabel("Training Repetition")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

axe.set_yscale(scale)

lines = axe.plot(range(len(self.errors)), self.errors)

return

def plot_errors_vs_weights(self, style="o") -> None:

"""Plots errors given weights"""

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Gradient Descent Mean Squared Error vs Weights")

axe.set_xlabel("Weight")

axe.set_ylabel("MSE")

lines = axe.plot(self.weights, self.errors, style)

return

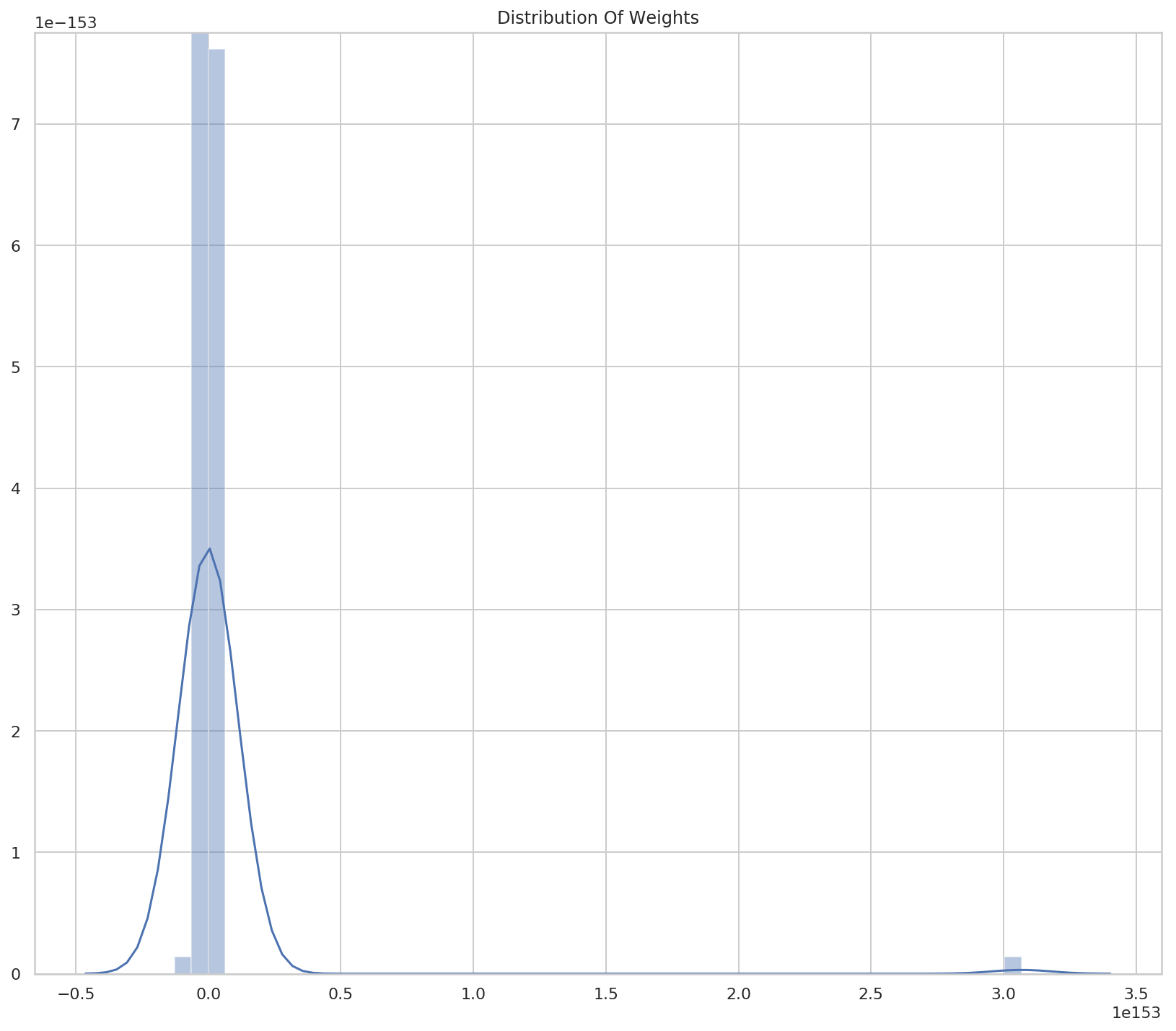

def plot_weight_distribution(self) -> None:

"""Plots the distribution of the weights"""

figure, axe = pyplot.subplots(figsize=FIGURE_SIZE)

axe.set_title("Distribution Of Weights")

lines = seaborn.distplot(self.weights)

return

def reset(self):

"""Resets the properties"""

self._errors = None

self._weights = None

self._predictions = None

self.weight = self.original_weight

return

Really Big Inputs

network = OneNode(weight=0.1, input_value=5, actual=0.1, print_every=30)

network.train()

Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.1 Step: 1 Weight: 0.1 Predicted: 0.50 MSE: 0.1600 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.1 Step: 30 Weight: -8.496029205125367e+38 Predicted: -4248014602562683567255766167412625375232.00 MSE: 18045628063585794511112671022597693816764790617265863683813015097617735965736960.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.1 Step: 60 Weight: -2.1654753676302967e+80 Predicted: -1082737683815148355196656106977575165473067380893761893846901009426287310965571584.00 MSE: 1172320891953392254658250331342439625964504567088377053437708818301948653571886896236931555371967400274585017142698424782066192956435576184566862647806273773371392.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.1 Step: 90 Weight: -5.51938258990998e+121 Predicted: -275969129495499010312802960568845701886516344963538842611688052470072992651229004282112996195046030793242534509005731004416.00 MSE: 76158960434503501277477316231095001035615545032300898123025508833954593912013767638712660721529293958181614329406854402338675069139074333788043867020532267345247209268079568592806683870329999393916410491701860464641755145654976460424275531137024.0000 (34, 'Numerical result out of range') prediction: 1.5336245888098994e+154 actual: 0.1

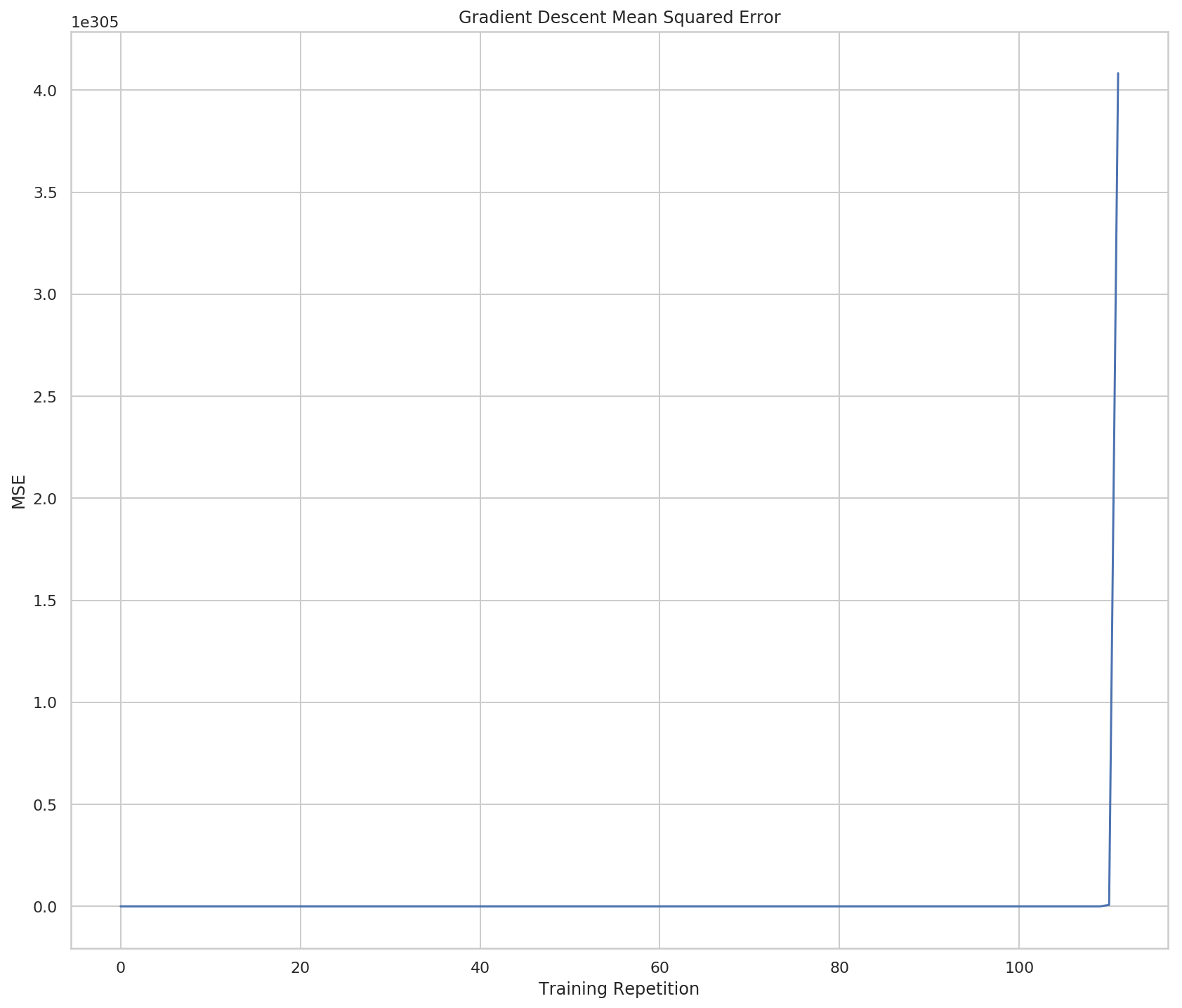

So, when the input is too big, the prediction explodes.

network.plot_errors_over_time()

It looks at first like there was no error and then all of a sudden it got huge - but if you look at the scale of the y-axis it maxes out at over \(4\times10^{305}\) and then the overflow error causes it to quit. So when the input is too large, the network goes out of control.

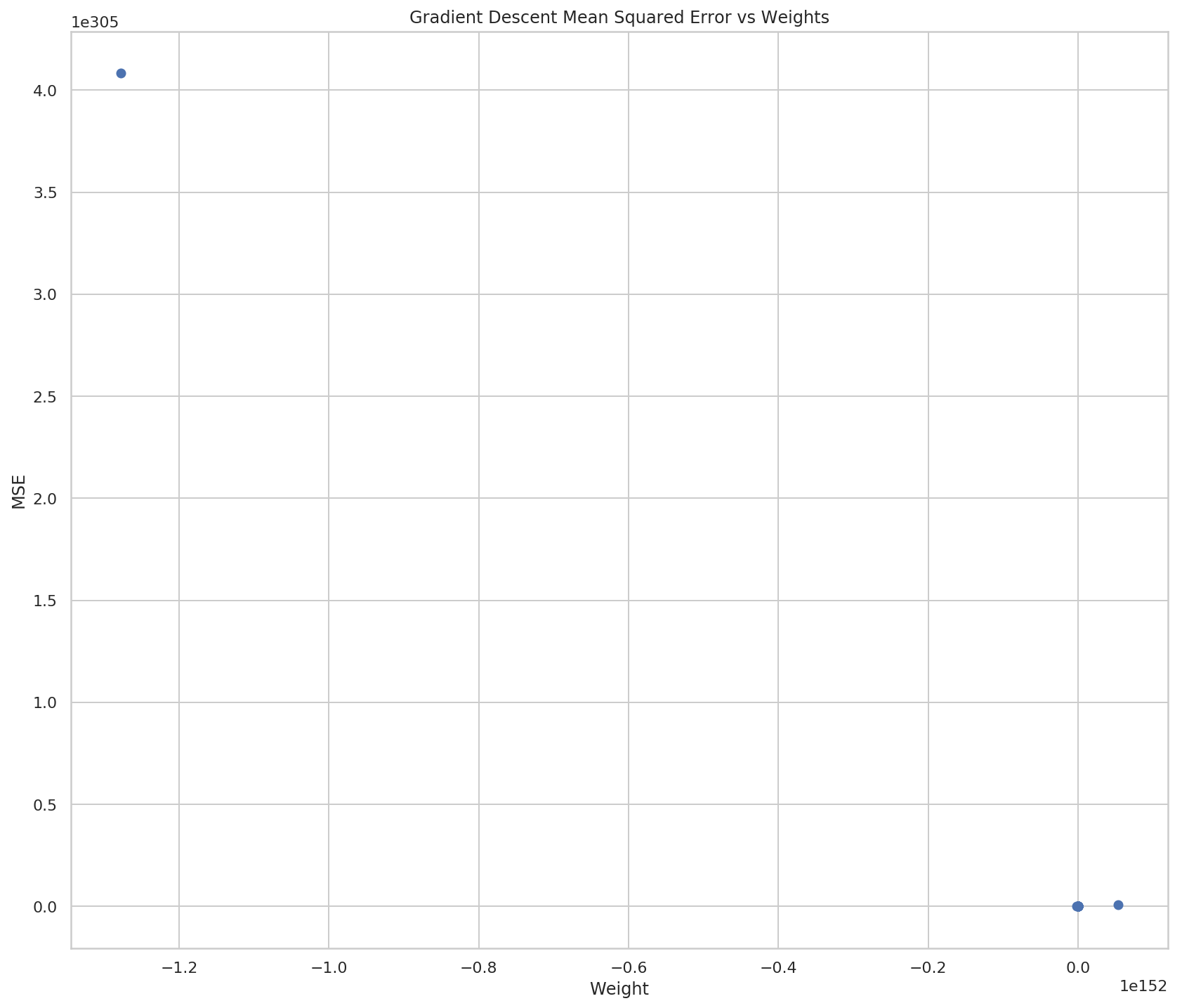

network.plot_errors_vs_weights()

So now it looks like there aren't really many weights, but if you look at both the X and Y scales you can see that they're really huge, so most of the points are probably centered around 0 (relative to the overall scale) and then all of a sudden they go crazy on the last two points.

So now it looks like there aren't really many weights, but if you look at both the X and Y scales you can see that they're really huge, so most of the points are probably centered around 0 (relative to the overall scale) and then all of a sudden they go crazy on the last two points.

figure, axe

network.plot_weight_distribution()

So we have a small number of weights that are very large. Or a lot of very large weights with a small number of very-very-large weights.

weights = pandas.Series(network.weights)

print(weights.describe())

count 1.130000e+02 mean 2.605805e+151 std 2.888965e+152 min -1.278020e+152 25% -6.526920e+74 50% -1.900000e+00 75% 1.566461e+76 max 3.067249e+153 dtype: float64

So the median is -1.9 and the mean is \(0.6 \times 10^{151}\). Looks like there are some outliers.

Fixing the Big Input Problem

The problem with big inputs is that they cause the gradient descent to explode. Remember our error function:

\[ error = input \times (predicted - actual)\\ = input \times ((input \times weights) - actual) \]

If the input is big the error will be big, and since our correction to the weights is based on the error:

\[ weights' = weights - error \]

our weights can start to swing wildly back and forth with the error growing larger and larger and swinginig between positive and negative numbers. The larger the input, the larger the error, the larger the derivative will be in the opposite direction.

The fix is to only update using a fraction of the correction. We find some value (\(\alpha\)) and multiply it by the change to reduce the influence any one change has. How do we find \(\alpha\)? Well, that turns out to be done by trial and error. If your error goes up as you train, then you probably have to make it smaller.

class AlphaNode(OneNode):

"""Incorporates weight update reduction

Args:

alpha: amount to weight the update

weight: the starting weight for the edge from the input to the output

input_value: the input to the node

actual: the actual output we are trying to predict

training_steps: how many times to train the model

tolerance: how close to zero we need our error to be

print_every: how often to print training status

stop_after: how many times to keep going after the optimal was found

"""

def __init__(self, alpha: float, *args, **kwargs) -> None:

self.alpha = alpha

__class__

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

return

def adjust_weight(self) -> None:

"""Takes the gradient descent step with alpha weight"""

scaled_derivative = (self.prediction - self.actual) * self.input_value

self.weight -= self.alpha * scaled_derivative

self.weights.append(self.weight)

return

Why does this help? Our problem is that the large inputs cause the gradient descent to overshoot past the value that would give zero error and by reducing the amount any one change can have we reduce the likelihood that this will happen.

alpha_network = AlphaNode(alpha=0.1, weight=0.5, input_value=5,

actual=0.8, print_every=30)

alpha_network.train()

Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 1 Weight: 0.5 Predicted: 2.50 MSE: 2.8900 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 30 Weight: -43463.41342612052 Predicted: -217317.07 MSE: 47227055374.1942 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 60 Weight: -8334186242.344855 Predicted: -41670931211.72 MSE: 1736466508118929965056.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 90 Weight: -1598089039844441.2 Predicted: -7990445199222206.00 MSE: 63847214481773219178788224499712.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 120 Weight: -3.064352661386353e+20 Predicted: -1532176330693176459264.00 MSE: 2347564308336405932287023519199639310958592.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 150 Weight: -5.875928686839428e+25 Predicted: -293796434341971398081118208.00 MSE: 86316344832056315635271476663737243674922770633850880.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 180 Weight: -1.1267155496783526e+31 Predicted: -56335777483917627928853446918144.00 MSE: 3173719824717480263078840848567916525595895306706307529098395648.0000 Optimum Reached at Step 0

Okay, so that still didn't work, maybe if \(\alpha\) was smaller?

alpha_network.alpha = 0.01

alpha_network.train()

Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 1 Weight: 0.5 Predicted: 2.50 MSE: 2.8900 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 30 Weight: 0.1600809572142104 Predicted: 0.80 MSE: 0.0000 Input: 5 Actual Output: 0.8 Step: 60 Weight: 0.16000001445750855 Predicted: 0.80 MSE: 0.0000 Optimum Reached at Step 34

So now our model is able to reach the correct value again. Can you figure out what the best \(\alpha\) is ahead of time? The magic eight ball says no. At this point in time the best way to find the hyperparameters for machine learning is to try them until you find the ones that perform the best.